THROWBACK POST: A down to earth talk about living in space

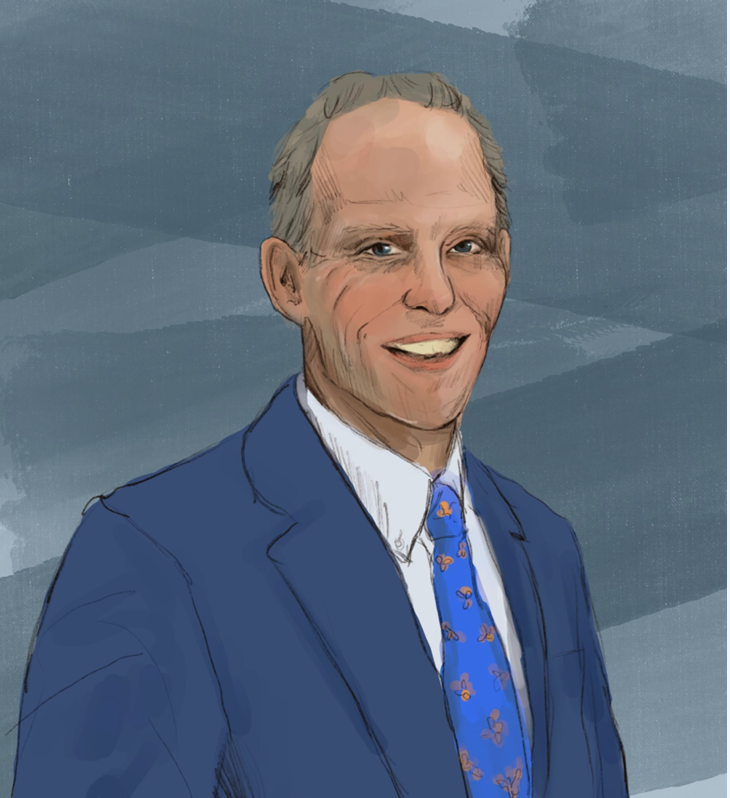

Photo by Hill Snapshots Chris Cassidy talking to the Hill community last Tuesday in the CFTA. Cassidy said afterward that he would go to Mars “In a heartbeat” if offered the chance.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally from Issue 1 of the 2015-2016 year, contrary to the date next to the byline.

Chris Cassidy, the chief of NASA’s Astronaut Office and a former Navy SEAL, spoke to the school about his experiences, earthly and extraterrestrial, during a very entertaining and enlightening hour last Tuesday evening in the CFTA. After being introduced by his friend Headmaster Zack Lehman, Cassidy presented Hill with a framed patch of the school crest, which he’d taken with him on a recent trip to the International Space Station.

Before his days as a risk-taker in the Navy and in space, Cassidy said he was a “normal kid” growing up in York, Maine. Cassidy’s brother, Jeff, Mr. Lehman’s roommate and best friend at Phillips Exeter Academy when the two were students there in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, said that his older brother’s interests, especially in the SEALs, “evolved gradually. By no means was he growing up as some crazy thrill seeker,” he said.

Cassidy attended the Naval Academy after high school and graduated in 1993. He earned his master’s degree of science in ocean engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2000, and then spent 10 years as a SEAL, recording over 200 hours underwater as the commander of several transport vehicles. “With training comes familiarity, and it became normal,” he said.

While training and working in the Navy, Cassidy met Bill Shepard, a former SEAL who had become an astronaut, and he began to think about joining NASA. “I just thought it’d be super cool to have the opportunity to go to space,” he said. “It was almost that simple for me to apply.” He was accepted into NASA’s astronaut program in 2004, but this was only the beginning of his long road to space. It took him two years to complete the training required to become an astronaut, which included sessions in the classroom and in a zero-gravity simulator.

Cassidy said the two jobs were connected because he took what he’d learned about teamwork from the SEALs to NASA. “You can be successful at both jobs by being a good teammate. Together, you accomplish the mission,” he said. “It boils down to teamwork, camaraderie and a close-knit unit. Those are the elements of success for both fields.”

Cassidy went into space for the first time in 2011 aboard the NASA space shuttle Endeavor STS 227. But his longest and most important voyage to date left Earth at the beginning of 2014 when he flew to the international space station on a Russian Soyuz rocket. One of the greatest challenges of this mission for Cassidy was the language barrier – the only language spoken or written was Russian.

But that wasn’t the only obstacle.

“Getting a space shuttle off the ground is a huge international effort,” he said. “Some anxiety happens a little bit on launch day, when you’re climbing onto a rocket that’s full of fuel, and they’re about to, on purpose, light it on fire. Anything bad can happen then.”

During their sixth month tenure at the space station, Cassidy and the crew worked on science experiments and maintenance projects. He went on several spacewalks, during which he and a team member went outside the station to inspect and experiment. His presentation in the CFTA covered the daily aspects of space life: how liquids, including urine, are recycled; the struggle of brushing your teeth in zero gravity; and what it feels like to realize that you’re traveling around the world every 45 minutes. He even gave advice as to how to successfully float through the cramped hallways of the station. “It doesn’t take much effort, it’s all about momentum,” he said.

Cassidy returned to Earth about a year ago, touching down in Kazakhstan after a nervy trip through the atmosphere. Although he had a window seat for the ride back, he admitted that it was “a little disconcerting to have thousand-degree plasma a few feet from your head.”

On the ground, Cassidy serves as the head of NASA’s Astronaut Office. He works at NASA headquarters in Houston and said he spends most of his time deciding which crew members to send on certain missions.

“Ultimately, it’s a management type of job, leading our astronaut corps to where we want to go,” he said. He also consults with engineers working on certain space equipment who seek astronaut advice.

Despite his position, Cassidy doesn’t ignore NASA’s problems, the biggest of which is its lack of government funding. “Every nation has a finite amount of money, and you’ve got to spend it where you want to,” he said. “It’s all about politics.”

It will be at least three years before Cassidy has the opportunity to go back into space. But when he does, his destination might not be the space station. With the continued privatization of the space industry and more corporate trips out of Earth’s atmosphere taking off every day, Cassidy said the question of whether or not a human will make it to Mars is no longer a matter of if, but when.

“We have all the technology, right now, today, to make it happen,” Cassidy said. “Everything that’s big like this costs money, and there’s not a funded program to make it happen.”

But how long will we have to wait until this new frontier is conquered? Cassidy says at least 15 years – the late 2020s or early 2030s – is when he expects the first Mars mission to take place. When it does, America can expect a reaction similar to the one caused by the moon landing in January 1969.

Cassidy is confident that the human desire for exploration will lead us to Mars. “Ultimately we are going to want to get off of planet Earth and explore, just as Columbus left Europe,” he said. The part he’ll play in this mission could be a big one – he might even be a member of the crew.

“I would absolutely consider going,” he said. “I’d go in a heartbeat.”