The Supreme Court poises to overturn affirmative action

Media: Adelyn Sim

The Supreme Court convened today and will decide whether race-conscious affirmative action in college admissions remains constitutional. Students bring the case on for Fair Admissions, a nonprofit, anti-affirmative action organization who successfully petitioned the Supreme Court in February 2021. SFFA accuses both Harvard University and the University of North Carolina of practicing discriminatory affirmative action policies.

Currently, many selective colleges consider race when deciding which students to admit, maintaining that these race-conscious programs ensure diversity on campus. Yet opponents claim these same policies are discriminatory towards both white and Asian, but primarily Asian, applicants.

For over 50 years and six SCOTUS cases, the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld race-conscious admission policies in college admissions. In fact, affirmative action seemed all but permanently settled. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg even stated in a 2016 interview with The New York Times, “I don’t expect that we’re going to see another affirmative action case.”

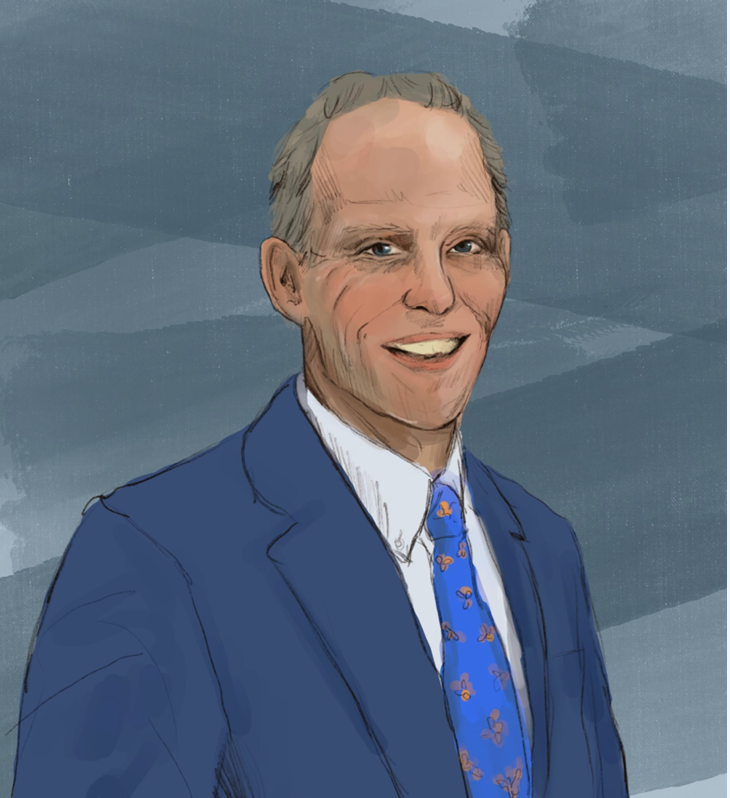

Yet the changing political makeup of the Supreme Court has recently renewed the case against affirmative action. With the arrival of three Trump-appointed conservative justices, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney-Barrett, the Supreme Court shifted to a 6-3 Republican supermajority. Given their prior overturn of Roe v. Wade, it is incredibly likely that this trio will strike down race-conscious admission policies. Even Chief Justice John G. Roberts, the most moderate conservative Justice in the court, has been an outspoken critic of affirmative action, writing in a 2007 opinion that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

While Chief Justice Roberts has occasionally joined the court’s liberal minority, such as on Roe v. Wade, his prior rulings make this exception slim to none. In the 2016 SCOTUS case Fisher v. University of Texas, Roberts joined the minority, along with Justices Alito and Thomas, both fierce critics of affirmative action. It is also important to note that the court’s decision to accept the case implies a major reversal in precedent. Because of a conflict of interest with Justice Jackson’s ex-position on Harvard’s board of overseers, Jackson voluntarily recused herself from the case, ensuring affirmative action’s demise.

It is almost certain that the Supreme Court will repeal affirmative action: so what does this mean?

According to proponents of affirmative action, if the SCOTUS rules race-conscious admissions unconstitutional, admission and enrollment of underrepresented minority students will dramatically decrease. After the state of Michigan banned affirmative action, the University of Michigan’s enrollment of black students fell from 7% in 2006 to less than 4% in 2021, a reduction of 44%. Native American enrollment was even more shocking. It fell from 1% before affirmative action to 0.1% after in 2021, a 90% reduction. “Despite persistent, vigorous and varied efforts to increase student body racial and ethnic diversity by race-neutral means,” the University of Michigan states, “the admission and enrollment of underrepresented minority students have fallen precipitously in many of U-M’s schools and colleges” since the overturn of race-conscious admission policies. This decrease in URM student enrollment also transpired in California after introducing Proposition 209, which struck down affirmative action in public colleges.

On the contrary, the end of affirmative action means a rise in white and Asian-American enrollment at elite colleges. According to a study published by UCLA, the data suggests that Asian-American students at UC Berkeley jumped from 37.30% in 1995 to 43.57% in 2000 following the ban on affirmative action. Since Proposition 209, the number and percentage of Asian-Americans has steadily increased at both UC Berkeley and UCLA. At UC San Diego, the number of Asian-American students increased from 35.93% in 1995 to 36.33% in 2000 and then 46.88% in 2005. In Texas, the Asian-American student population increased from 14.26% in 1995 to 17.74% in 2000, while in Florida, Asian-Americans at the University of Florida increased from 7.50% in 1995 to 7.84% in 2000, and to 8.65% in 2005.

In The New York Times 2013 internal review of the university’s admissions, Harvard University conceded that if the university only considered academic achievement, “the Asian-American share of the class would rise to 43% from the actual 19%. After accounting for Harvard’s preference for recruited athletes and legacy applicants, the proportion of white students increased, while the share of Asian-Americans fell to 31%. Accounting for extracurricular and personal ratings, the share of whites rose again, and Asian-Americans fell to 26 percent.” If the SCOTUS rules race-conscious programs unconstitutional, then overall, Asian-American, albeit mostly white, enrollment will increase.

In fact, Harvard’s own research division found that Asian-American admission rates were lower than those of whites, despite Asian-American applicants outperforming whites in every category besides the vague, subjective, and biased “personality rating,” an unclear standard for judging an applicant’s personal character.

As a result, SFFA argues that the end of affirmative action is a necessary and long overdue decision that will finally end systemic discrimination in college admissions. In a court filing, SFFA claims that “an Asian-American male applicant with a 25% chance of admission would have 35% chance if he were white, 75% if he were Hispanic and a 95% chance if he were black.”

The overturn of affirmative action not only affects college campuses, but also the diverse landscape of the Hill. Some students on campus believe that the overturning of affirmative action would level the playing field for college admissions.

“While I think the decision to overturn affirmative action might be a good thing, I don’t think this is the end of AA, merely the beginning of a renewed conversation on the topic,” Patrick Dunn ’23 said.

“I think a ban on affirmative action would be great since it gives equal opportunity to all,” Logan Ray ’25 said.

Yani Lin ’25 argued that affirmative action has never gone far enough to address racial disparities in the college admissions process. “While I support the overturn of affirmative action, I do believe that more needs to be done to help people—especially minorities—in need,” Lin said. “For me, I think affirmative action is just a bandaid to a more systemic problem in America than a solution.”

Others found the case catastrophic. Neil Thompson ’25 slammed the case: “I think if the Supreme Court bans affirmative action, it would be terrible. I think overturning affirmative action would remove a lot of opportunities for minorities to advance in today’s society.”

Some students also argue that overturning affirmative action would fundamentally change the cultural landscape on college campuses.

“The Supreme Court banning AA would be a detriment to college diversity,” Bash Bashiru ’25 said.

Whether you love it or hate it, the Supreme Court is likely to bring an end to over forty years of race-conscious admission practices. This court case signals a broader trend of the Supreme Court’s willingness to revert decades of its own precedent—such as with Roe v. Wade. “On the things that matter most,” said Irv Gornstein, executive director of the Supreme Court Institute at Georgetown Law School, “get ready for a lot of 6-3s.”