Toxic gratitude is a pandemic at Hill

There’s a common misconception about gratitude. It’s a dangerous one that has existed as long as the term itself but has been especially exposed in light of the pandemic. To best understand the harm of this outwardly positive practice, it is important to recognize the present climate of the world. There are many terms that come to mind when trying to describe the current global state, a few in particular being: overwhelming, disappointing and anxiety-inducing. Perhaps the most important and necessary word to use, though, is traumatizing.

The very definition of a pandemic denotes something problematic as prevalent on a global scale and is therefore recognized as a serious and legitimate form of trauma. For many on this campus, COVID-19 might be their first time enduring a traumatic experience. They might not have the tools to define what they are feeling, to identify their changed behavioral patterns, or to muster up the emotional courage to be vulnerable with their peers. It’s realities like these that make our words and actions as a community that much more crucial.

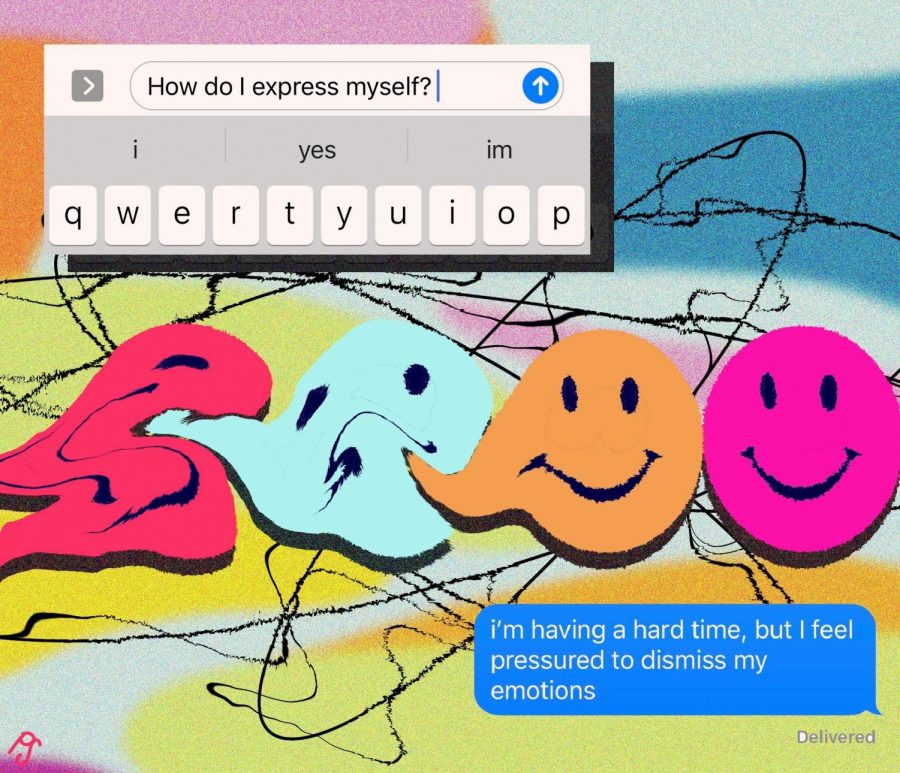

The misconception with gratitude is that it’s the first step to healing, rather than the final destination. We, as humans, have this tendency or instinctual desire, if you will, to rectify what feels wrong. For example, when we feel bad our first thought is wanting to feel good again. To translate that into modern terms with COVID-19, when things feel overwhelming, disappointing or anxiety-inducing, our minds go to this place of wanting to push those feelings away and replace them with thoughts of gratitude. These show up as general and often disingenuous platitudes such as: “I should be grateful right now” or “people worked hard to get me here.” These remarks aren’t bad, per se, as they can serve as worthy affirmations, but, when substituted for or used as a means of invalidating one’s grief and processing, they can be detrimental.

When asking Hill students if they’ve been reached by this notion of toxic gratitude, Lauryn Fudala ’21 said: “My roommate and I are prefects in Dell, so naturally we’ve been feeling pretty isolated this year. We’ve been told by a lot of faculty that we should be grateful that we’re even here on campus, but the reality is that we’ve both been really struggling to come to terms with everything. Am I grateful? Absolutely, but I shouldn’t use gratitude to invalidate how I feel about my current situation.”

When asked what the ideal response from faculty and her peers would be, Fudala answered: “I hear you. I’m sorry you feel that way. Can you tell me more about it?” What it suggests is that what we need as a community isn’t to be fixed or advised, but rather empathized with, heard, and validated.

At a school that prioritizes its close-knit community above all else, it’s most important that we dispense our energy trying to serve it, rather than trying to tell it how to feel. Yes, we should be grateful. I know I am, as are many of my peers, but it is possible to be both grateful and struggling. I pose to you, not a question of which one’s more important, but rather which one should come first and the difference that prioritization can make. What if we as a community listened more? What if instead of telling others how they must serve we asked how we can serve them? What would that look like? It’s possible that if we put these ideals and questions to practice, we could cultivate a very real sense of gratitude on campus, one that doesn’t require reaffirmations.